Exclusive: American filmmaker exposes Israel’s war on Palestinian journalists

Robert Greenwald says wearing press vests in Gaza does not protest journalists but make them targets

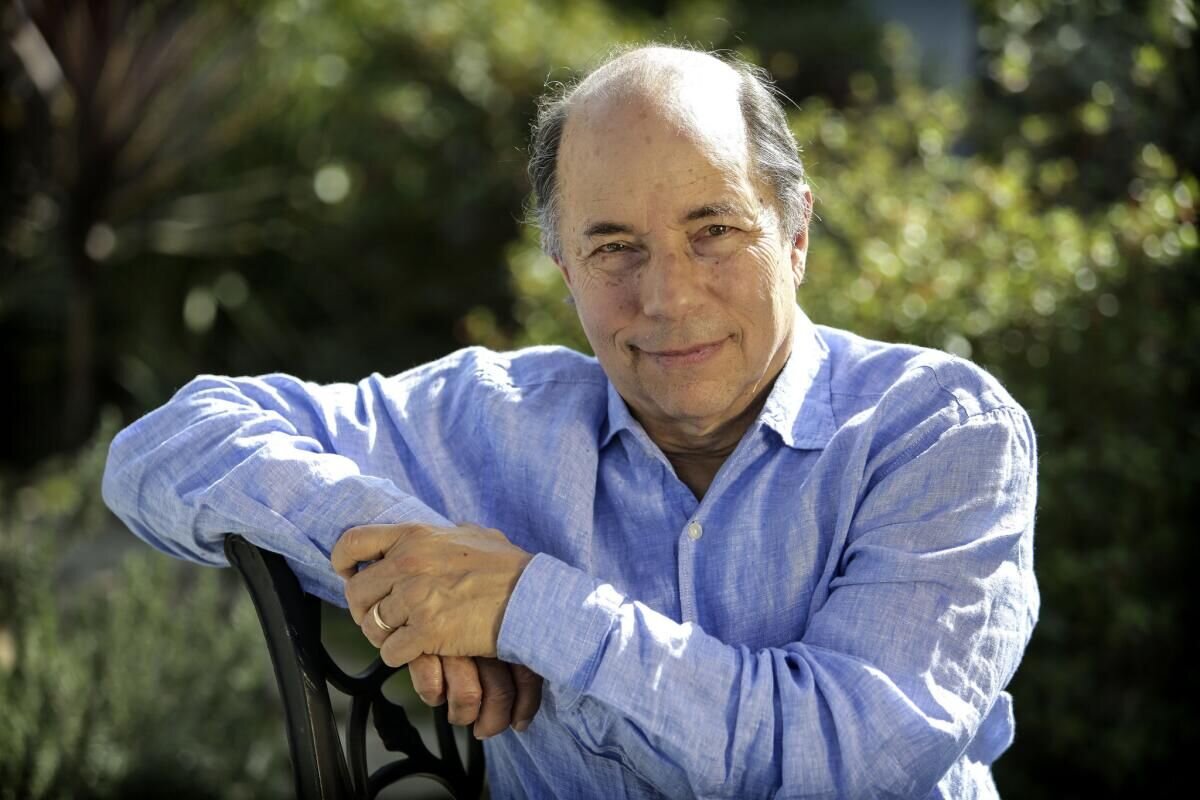

TEHRAN - In an exclusive interview with the Tehran Times, American filmmaker Robert Greenwald sheds light on the untold stories of Palestinian journalists who have been systematically silenced during Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza.

Greenwald, a Jewish filmmaker based in New York and founder of Brave New Films, has dedicated his latest documentary to humanizing the lives of three slain journalists—Bilal Jadallah, Hiba al-Abadbadal, and Ismail al-Ghul—whose stories embody both the resilience and vulnerability of Gaza’s press under relentless Israeli bombardment.

Greenwald explains that his project was born out of a dual realization: that numbers alone cannot convey the human cost of war, and that journalism itself has become one of Israel’s battlegrounds.

Since October 2023, more than 240 journalists have been killed, many while wearing clearly marked press vests or sheltering with their families.

For Greenwald, such killings are not accidents but part of a broader effort to eliminate voices that contradict Israel’s narrative and to sever Gaza from the global flow of information.

By combining personal archives, social media footage, and split-screen contrasts between Gaza’s vibrant past and its devastated present, Greenwald’s documentary underscores the moral imperative of defending press freedom. He insists that while governments may turn a blind eye, independent filmmaking can break the silence and mobilize global action.

The text of the interview is as follows:

1. As a Jewish filmmaker from New York who has long taken on controversial subjects, what personal conflicts or revelations led you to humanize the stories of Palestinian journalists in Gaza?

I was seeing and reading more and more commentary from the brave people in Gaza, and I was increasingly upset and concerned and motivated to try to do something and tell the stories.

Now the question is, what could I do, what could we at Brave New Films, as a very small U.S.-based non-profit, do? And I realized that the haters—the people who hate Palestinians, the people who are racist around the issue of Palestinians—we were never going to reach them, and we were never going to convert them. But in the United States there are millions of people who hadn’t paid attention to the issue, didn’t care about the issue, and so I decided on a two-fold approach.

One is journalists, and my assumption was that even people who were not focused on the issue would not be in favor of killing journalists.

Number two, rather than limiting it to numbers, which are abstract, I thought—and I believed, and it’s consistent with the other work we’ve done at Brave New Films—that if we could humanize these journalists, if we could bring them to life even though they had been killed, using social media, using video, we could impact an audience in a way that they were not impacted only by putting up a horrible number of journalists who have been killed.

Those two factors came together, and then an additional element—overlay, if you will—was the fact that I felt a deep responsibility as a person raised in New York, a person who culturally is Jewish, and who personally felt this is a deeply moral issue. And so all those things came together, and the result was months and months of artwork and the film, which is now available for free to anybody all around the world.

2. By focusing on these three journalists—Bilal Jadala, Hiba al-Abadbadal, and Ismail al-Ghul—you put a face on policy. How did you choose these stories to humanize the Gaza crisis, and what impact do you hope they have in light of recent journalist deaths?

Well, in terms of the impact, when you work in the world I do, which is social justice using film, and it’s both the full film as well as social media—we’re on all the platforms.

We reach about a million people regularly between all of the platforms. My own personal platforms that I’m on, and Brave New Films is on many platforms. A combination reaches about a million people regularly, and the belief was that our impact would be longer term, even though I wish I could stop the killing today.

That’s not the case. The goal is to affect people’s opinion, to inspire them to take action, and to move the many people in the United States to connect to their elected officials and get their elected officials to stop funding the war. If the United States were to stop funding the war, I believe it would be over almost immediately.

So that’s the hope. In terms of the impact, it’s hard to know exactly. What we do know—there are polls in the United States that have shown an extraordinary shift in a relatively short period of time, going from “100% Israel could do no wrong, everything they do is right” to now a radical reduction in that support—and it will continue.

The work is not over. It’s an effort to reach people. By the way, not just in the United States—we’re working to reach people all over the world.

We’ve had screenings in Israel; I hope we’ll be having more screenings there. In terms of the first part of your question—how did we choose these three? It was a long and challenging process, because so many journalists have been killed.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, or CPJ as they’re known, have an extraordinarily effective website which lists each of the journalists who have been killed, which provides background information about each of them. So we started with their website, which had at the time maybe 130–140 people, and we started looking for the stories which had a variety of people doing a variety of tasks.

Some were on camera, some were researching, some were think tanks, and then most critically, in order to bring them to life through social media, was a deep dive into each of the possible people’s personal videos that were publicly available.

And that was key for us, because if she or he had not been active in social media, if there weren’t videos of family, friends, colleagues, children, then we wouldn’t be able to bring them alive.

So that became the final and determining factor, and it’s what you see in the film—which is human beings, children having birthday parties, families being torn apart, workplaces being destroyed, but again, over and over again, how to make the people as individually human as possible through the accurate telling of their lives and their stories.

“Starvation in Gaza has moved people in the United States in a way they hadn’t been moved prior to that.”

3. The split-screen technique contrasting Gaza’s vibrant past with its current situation bypasses Israeli censorship. How did your crew develop this approach, and could it further amplify the stories of journalists killed in recent strikes?

Yes, I think that, and again, we’re seeing a lot on social media. In terms of the recent killing of journalists, including Anas—who’s in the film briefly—there seems to have been an increased outcry in the United States among press, among media, and from my perspective, it’s been a combination of factors.

One has been the horrible starvation that Israel is imposing on Gaza, because it’s an image, because it’s a visual—because other than a few people who are lying or pretending it doesn’t exist—you see images, particularly of children who have been starved, some of them starved to death.

That has moved people in the United States in a way they hadn’t been moved prior to that. Then on top of it, you have the killing of a well-known journalist, well-known in some parts of the world, and the fact that Israel acknowledged they had targeted him.

It was not an accident, it was not a sidebar. They targeted him, and they targeted him saying, as they say almost every single time, “Well, he worked for Hamas.” But there is no evidence. They provide no evidence, and one of the arguments—which I think is very effective—is: if you’re telling us this, let in international journalists, or substantiate; let them come in and look and investigate. Israel has not done that.

They have killed Palestinian journalists, they have not allowed any international journalists in, and then they claim that almost in every case it was Hamas. So what I ask is: were the 17,000 children who’ve been killed, were they all Hamas? What I ask is: the medical workers who’ve been killed, were they all Hamas? What I ask is: the hospitals that have been destroyed, the schools that have been destroyed—were they Hamas?

So it’s an argument that will not bear up, and it’s an argument that I believe, and hope, and work to spread to as wide an audience as possible.

4. Your documentary humanizes Bilal Jadallah’s mission to empower reporters through Press House Palestine. How did his story shape your narrative, and what does it reveal about the broader risk journalists face in Gaza today?

I think all three of the stories, and the hundreds of journalists who have been killed, make a very clear statement: journalists with extraordinary courage are trying to do their jobs, are trying to be truth seekers, and they’re being killed. And in some cases there are—I don’t want to say replacements—but there are other journalists who are stepping into the void and continuing to tell the story.

Again, here is where our phones, our social media—Instagram particularly—has an incredible number of people who are in Gaza, who are videoing, talking, witnessing, and telling us: here is the reality of what’s going on, and here are images, here are stories.

We need everyone’s help, whether it be politically, socially, economically. There are many things that people can do, and I hope we will activate them to do so.

5. Your team’s deep dive into social media for authentic footage of slain journalists is a hallmark of the film. What was the most challenging moment in portraying the tragedy of the life and death of these three journalists for you?

I would say that it was on two levels. One, on a personal human level: when you spend months looking at people’s social media, seeing their varying cases—mothers, fathers, uncles, aunts, children, relatives—when you see them doing their work, and as you’re working on it day after day, week after week, month after month, you know these people have been killed, and that takes the personal toll.

Now, let’s be clear: whatever personal emotional toll it took on myself, on the team working on it, is nothing in comparison to what the people in Gaza are being subjected to. But the hard part is staying focused, staying objective, staying fact-based, in order to tell the personal story as effectively as we’re able to.

6. The film’s haunting theme of press vests becoming targets resonates with a recent report of journalists being struck despite clear markings. How does this reinforce your argument about deliberate efforts to silence Gaza’s voices?

When I began working on this campaign and film, I assumed that the press vests, as well as the markings on the press vehicles, were an indication, in a way, that journalists could be safer. I’m a New Yorker—not a lot of things shock me. That really shocked me: that the journalists themselves, in throwing down the vests, making a very coherent argument, that not only do they not protect them, but they serve as targets.

That was both troubling and shocking, and educational in the sense of my learning something that I did not know.

7. One of the parts of the film that touched me personally was about Ismail Al Ghul's journey. In his journey from his daughter's birth to her kissing his grave, it was a very poetic highlight in this documentary. How did you craft this narrative to connect with global audience and what does it say about the personal toll on journalists in conflict zones?

I felt when I saw the clip of his daughter’s birthday, when I saw the clip soon after she was born, it moved me very much. I have children, I have grandchildren, and I felt that clip, and—as you just said—it could reach many people who are human beings.

Whether you have children or you know children, whether you’re an uncle or an aunt or a grandparent or a parent, the notion of that experience with a child is a universal experience, and I believe strongly if we could tell that story authentically, without manipulation, using the existing footage, we could reach a wider audience, and it could tell people: without our being preachy, without our being lecturing, here is the reality of what it means. A father with a daughter whom he deeply loves was prepared to continue doing the work, even though he knew there was the possibility of death.

That’s what we see, and that’s what we portray, and that’s what is moving people around the world in different languages, in different cultures, in different backgrounds.

8. With over 500 free screenings worldwide, how do you hope your documentary will mobilize viewers to act, especially given the Committee to Protect Journalism warning about escalating attack on Gaza's media?

As we speak today, we’re over 900 screenings around the world, which is wonderful and keeps growing. The fact that, thanks to our donors and sponsors, we’re able to make it available for free to everyone—I think it’s very important, and there are a variety of ways that we can affect change.

One particular is in the United States: Senator Bernie Sanders has been extraordinary in bringing up for legislation a series of different bills that would limit, change, stop some of the financing of the war. Senator Sanders has also connected it to the moral imperative, to the emotions of what is going on there. So there’s the legislative approach: encourage, support, criticize elected officials who are not doing the right thing in the United States.

There is social justice advocacy work, there are demonstrations, there are protests, there are phone calls, there are letter-writing campaigns, and there is the media—reaching out and telling people, encouraging people to cover it, to write stories, and to help spread the word—so that the more people see the film, the more varied actions there will be.

Senator Sanders, again, has led the awareness and encouraged people, encouraged elected officials not to take any money from AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee), which is an organization in the United States that provides millions and millions of dollars to candidates who are 100% of the “Israel can do no wrong” school. Senator Sanders is starting to see some shift.

A few days ago, there were two or three members of the House of Representatives in the United States who had gotten AIPAC money, but they changed their position. They now said they will not take the money, and they will be critical of what Israel is doing. So, there are, I’d say, multiple efforts, multiple levels.

Change doesn’t come in one bucket or in one way. It comes in multiple ways.

“I believe the more the (Israeli) horrors go on, the more people become aware, the more there will be further pressure to protect the freedom of the press.”

9. Facing meta-censorship of your films, ads, and funding struggles, how do these barriers mirror the information blockade in Gaza, and what lessons can be drawn for advocating press freedom today?

Well, press freedom has never been more important. And to me, it seems so obvious.

And this is the worst, in terms of the journalists who are being killed. It’s not the only issue with press freedom. It’s in many countries, including the United States, in many different forms, in many different ways.

So, I hope, I believe, I think that anybody concerned about this issue and understanding how extraordinary it is—Palestinian journalists being killed, international journalists not being allowed in—it’s a lesson to all of us of why press freedom is so, so crucial.

And I believe the more the horrors go on, the more people become aware, the more there will be further pressure to protect the freedom of the press, to protect the lives of the press, and to do what each of us can. And everybody can do something to continue in both protecting and expanding the freedom of the press.

Mr. Greenwald, I would like to ask you to address our audience directly and tell them what is the most important message you hope the viewers take away from this documentary, especially in light of the recent escalation of targeted attacks on journalists in Gaza?

I hope that everyone from your audience, first of all, sees the film. They’re able to go to our website.

You know, there’s a line I have above my desk: “Awareness is the first step to change.”

So we need that to begin with. After people have seen the film, I think they know much better than I do what they can do. Is it writing a letter? Is it making a phone call?

Is it interacting with their own government to do any one of the steps that can help stop the killing, stop the starvation, and bring the war to an end—at the same time as encouraging long-term freedom of the press and having press alive and well and doing its job.

* For readers interested in learning more about Gaza: Journalists Under Fire and the ongoing global campaign, here are selected materials provided by director Robert Greenwald:

- 🎬 Official Trailer: https://www.bravenewfilms.org/palestinianjournalists

- 📝 Signup Form: https://bit.ly/palestinianjournalists

- 🌍 Screenings: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMngbgG3j00&feature=youtu.be

Leave a Comment